OII Research Fellow Rebecca Eynon and Anne Geniets discuss the topical issue of the UK’s digital inclusion strategy, discussed at last week’s OII workshop on low and discontinued Internet use by young people in Britain.

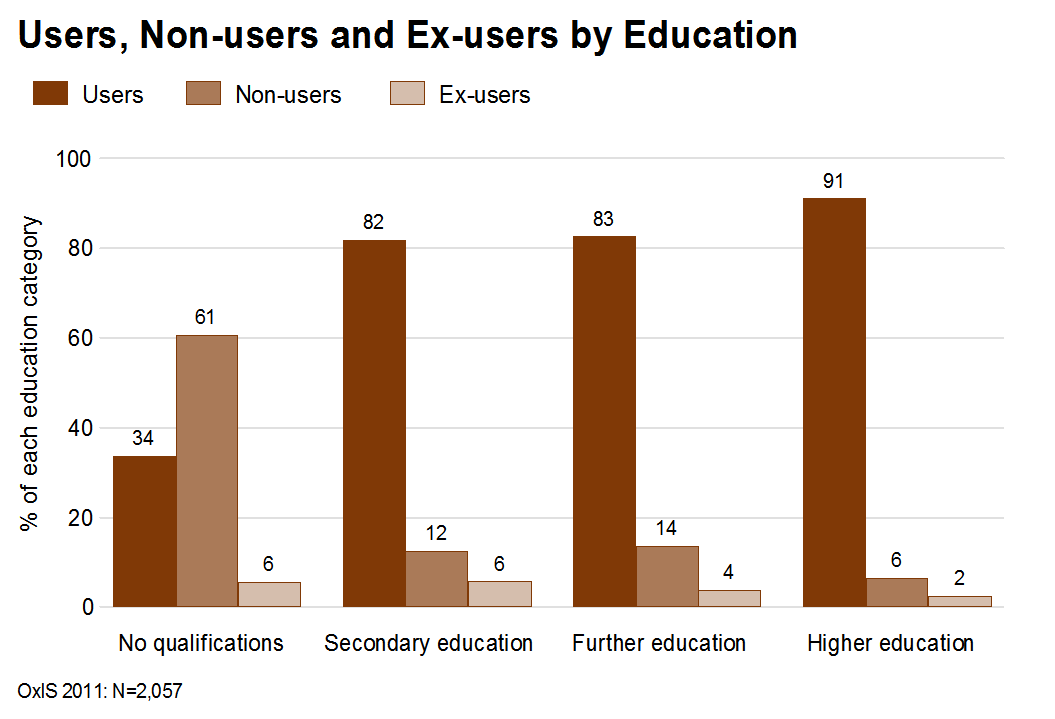

On 23 March 2012, the Oxford Internet Institute saw stakeholders from a variety of backgrounds, attending our workshop ‘On the Periphery? Low and Discontinued Internet use by Young People in Britain: Drivers, Impacts and Policies’. One of the key themes that emerged over the course of the day was that digital inclusion cannot be addressed without tackling social exclusion, for many of those who are currently not online are also socially excluded. <hr />

The Government’s recent digital inclusion campaigns seem at first sight to recognise this need. For example, the UK ICT Strategy paper pledges that “The Government will work to make citizen-focused transactional services ‘digital by default’ where appropriate using Directgov as the single domain for citizens to access public services and government information. For those for whom digital channels are less accessible (for example, some older or disadvantaged people) the Government will enable a network of ‘assisted digital’ service providers, such as Post Offices, UK online centres and other local service providers” (section 45, UK ICT Strategy 2011).

‘By default’ strategies are at the core of a concept called ‘libertarian paternalism’, which initially was advanced and popularized by two American academics, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, and since has been adopted by a number of governments around the world. In the UK, it has inspired the creation of the Cabinet Office’s Behavioural Insight Team, commonly known in Whitehall as the ‘Nudge Unit’.

The idea behind the libertarian paternalism concept is that the government gently encourages citizens to act in socially beneficial ways, without infringing their freedom or liberty, and through these nudges it improves economic welfare and well being for the whole of society. Governments nudge by reorganizing the context in which citizens make certain decisions, a strategy also referred to as ‘choice architecture’. To quote a common example, it may not be at the forefront of learner drivers’ mind to sign up for the organ donor register, but by asking learner drivers whether they would like to join the register at the end of their application for a provisional driving licence, many learner drivers may choose to opt in. In other words, while the learner drivers are by default not enrolled as organ donors, they are gently ‘nudged’ by authorities to join the organ donors register and to help tackle the nationwide shortage of organ donations.

To apply libertarian paternalism to issues where citizens have the freedom to make a choice is sensible. Libertarian paternalism after all already has proven to be beneficial in a number of aspects of civic life. But by applying the concept to issues where citizens do not have a choice because of restricted resources, by default strategies risk becoming a tool for social exclusion. This poses a democratic problem.

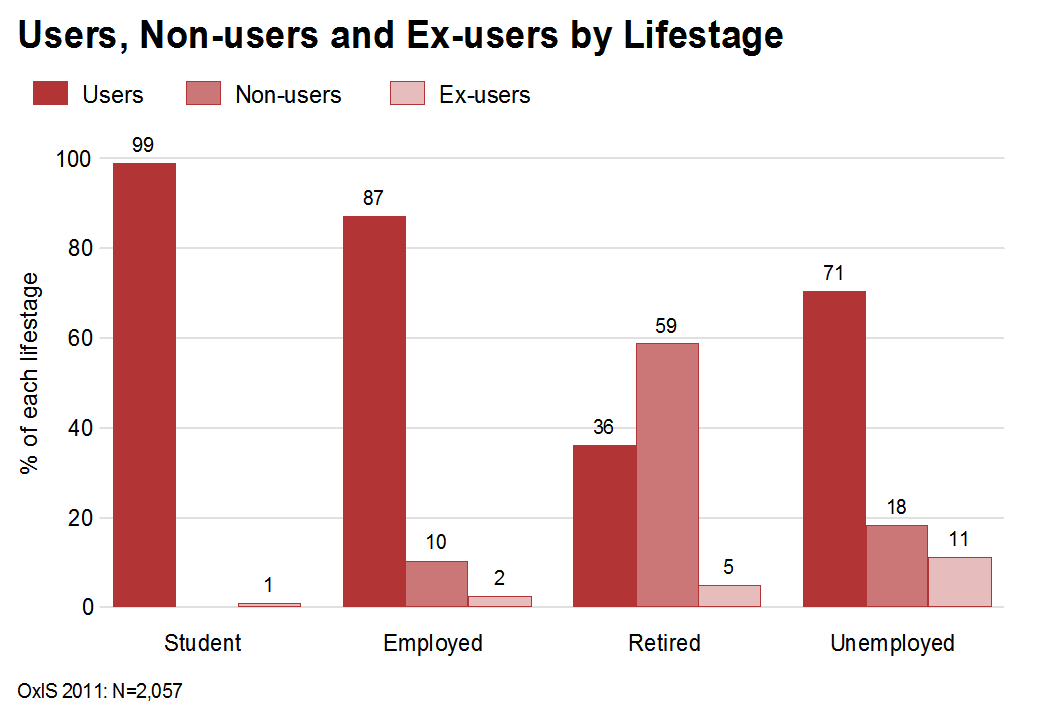

This, our research suggests, is a current threat for young people who are high users of government services but infrequent users of the Internet.

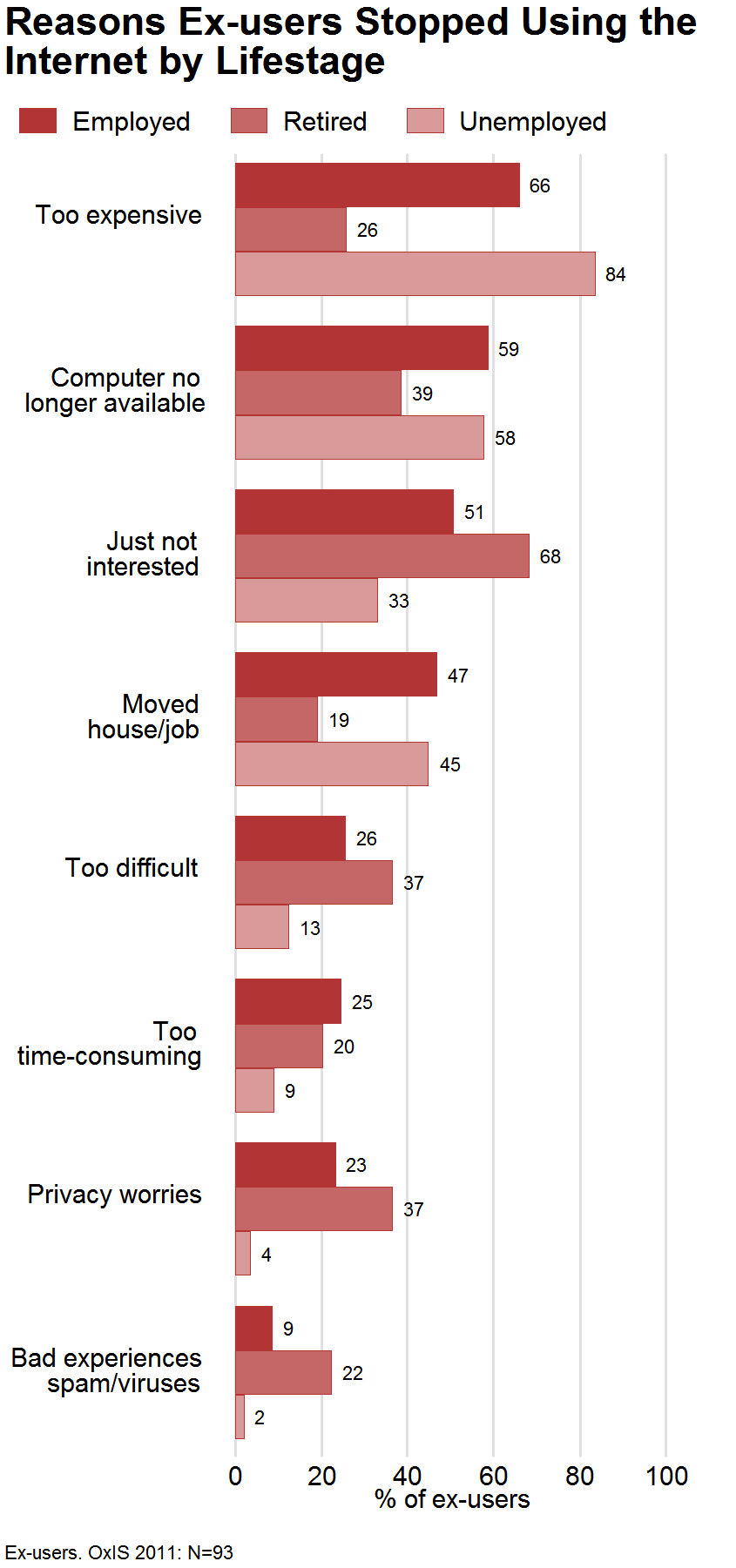

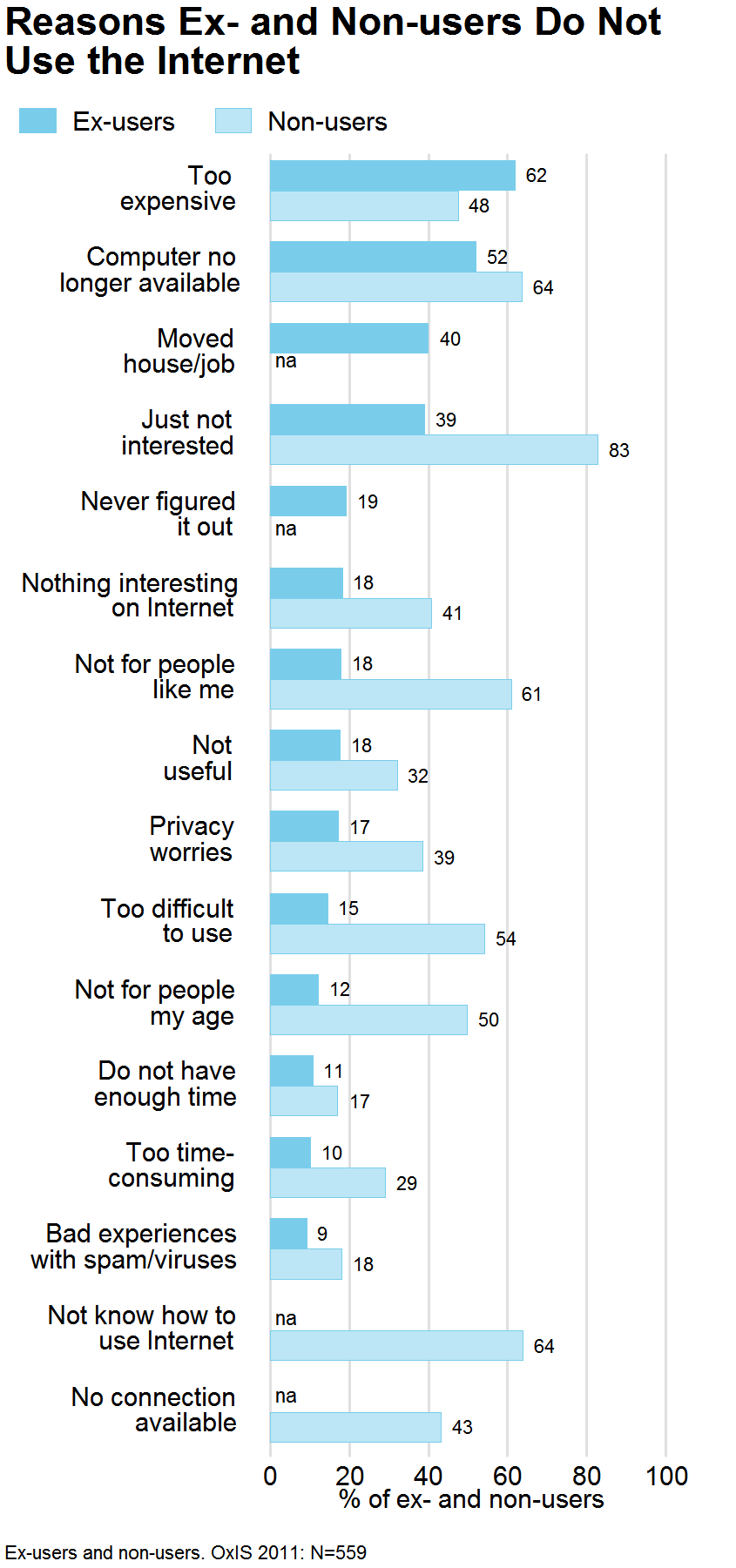

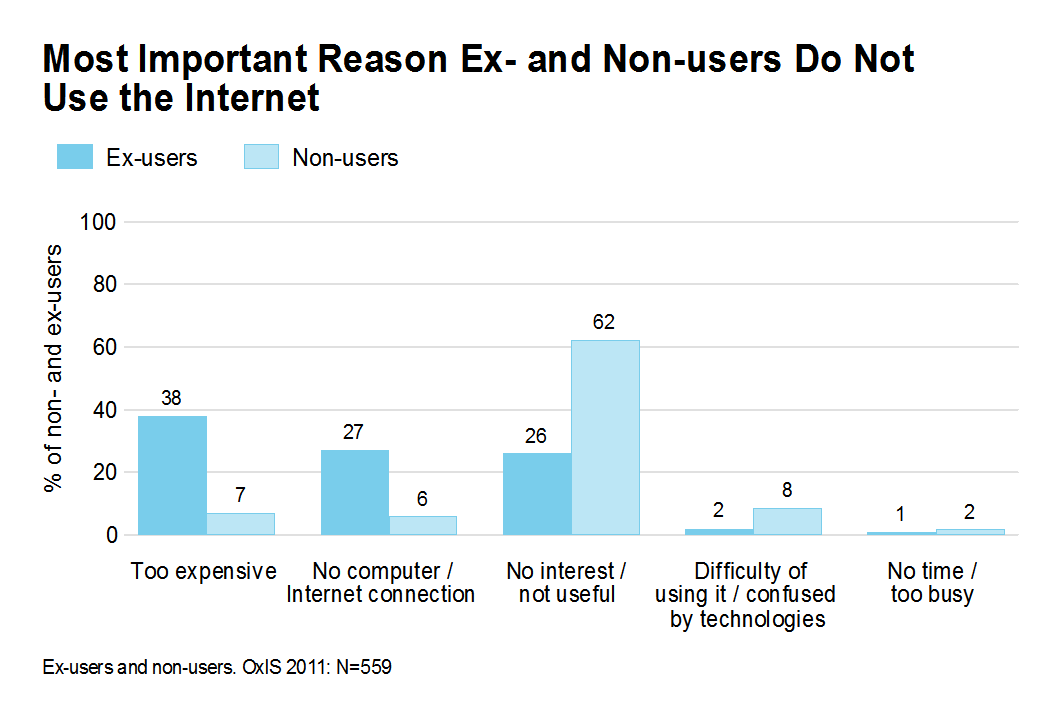

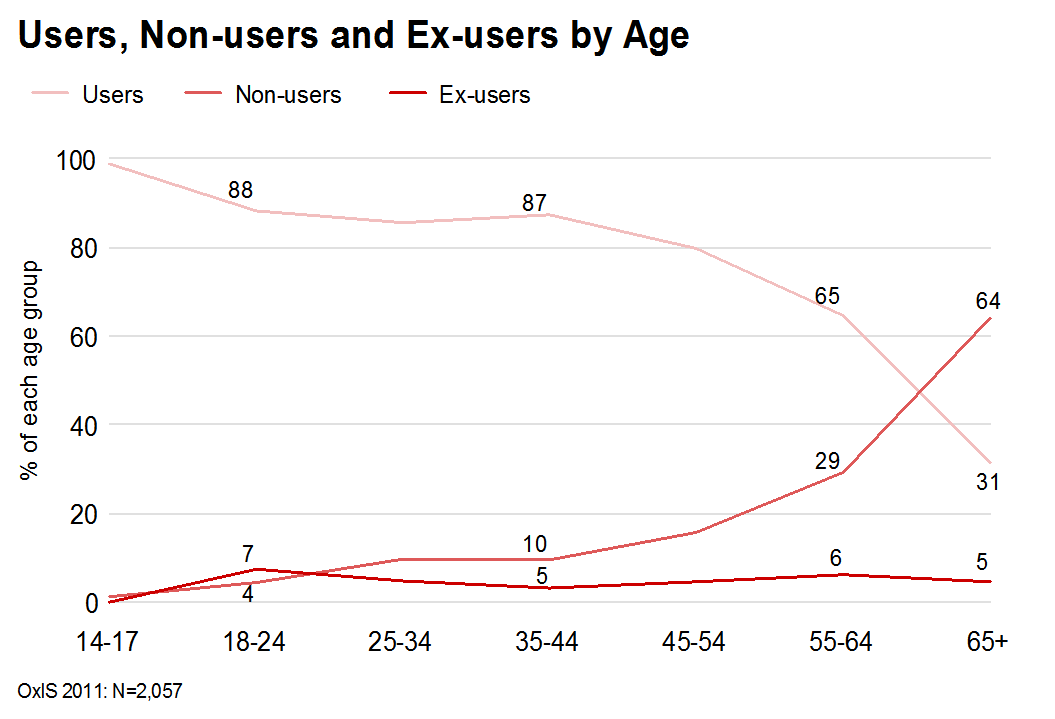

The benefits of moving government services online are clear. Older citizens who do not go online often do not do so due to a range of factors, such as lack of skills, lack of interest or absence of an Internet connection. While these reasons are complex, there is often, at least to some extent, some element of a digital choice. Thus, for many people within this group, digital by default strategies that encourage citizens to use the government’s online services may work well. For example, through the provision of support at UK online centres and initiatives such as Go On Give an Hour in the context of the UK Race Online 2012 campaign.

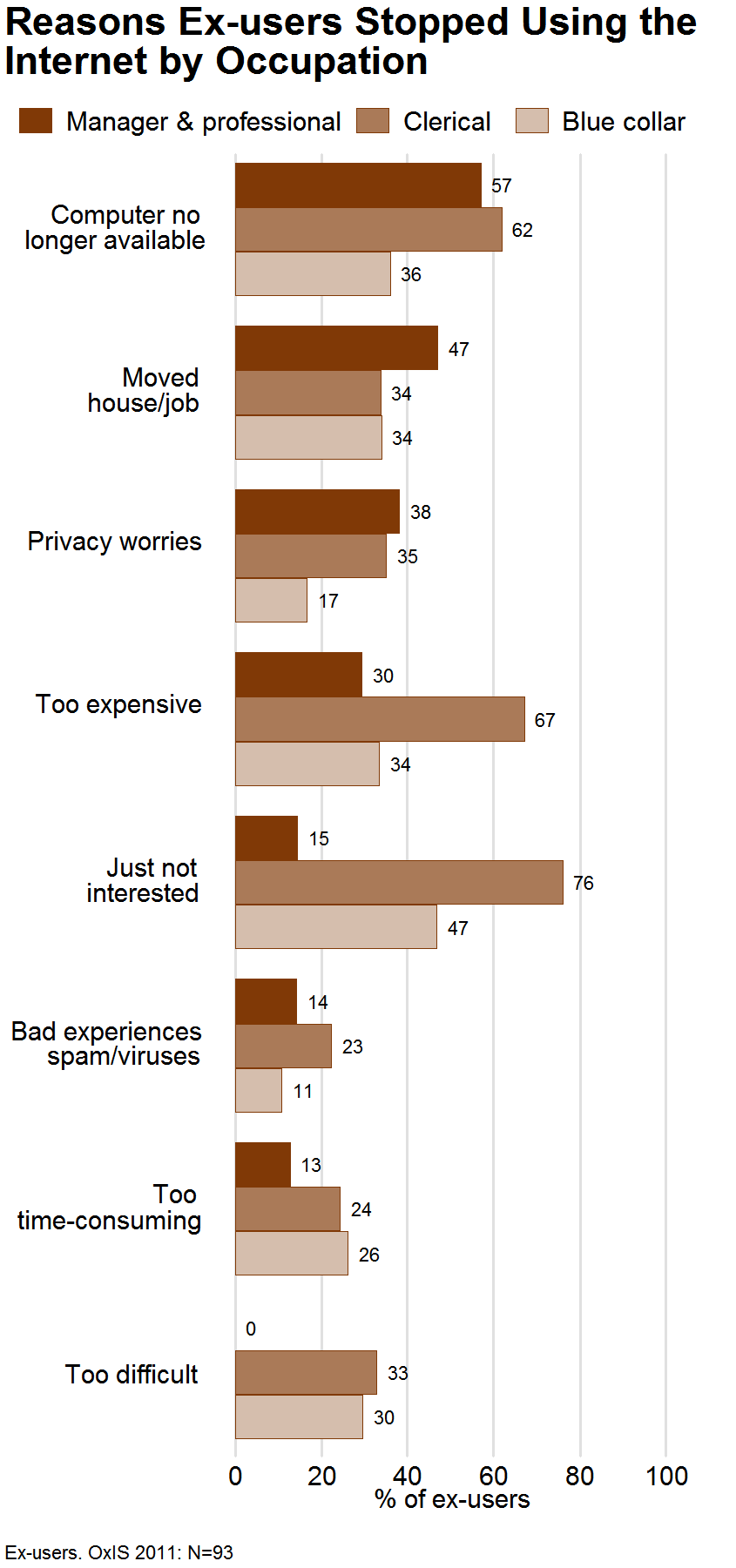

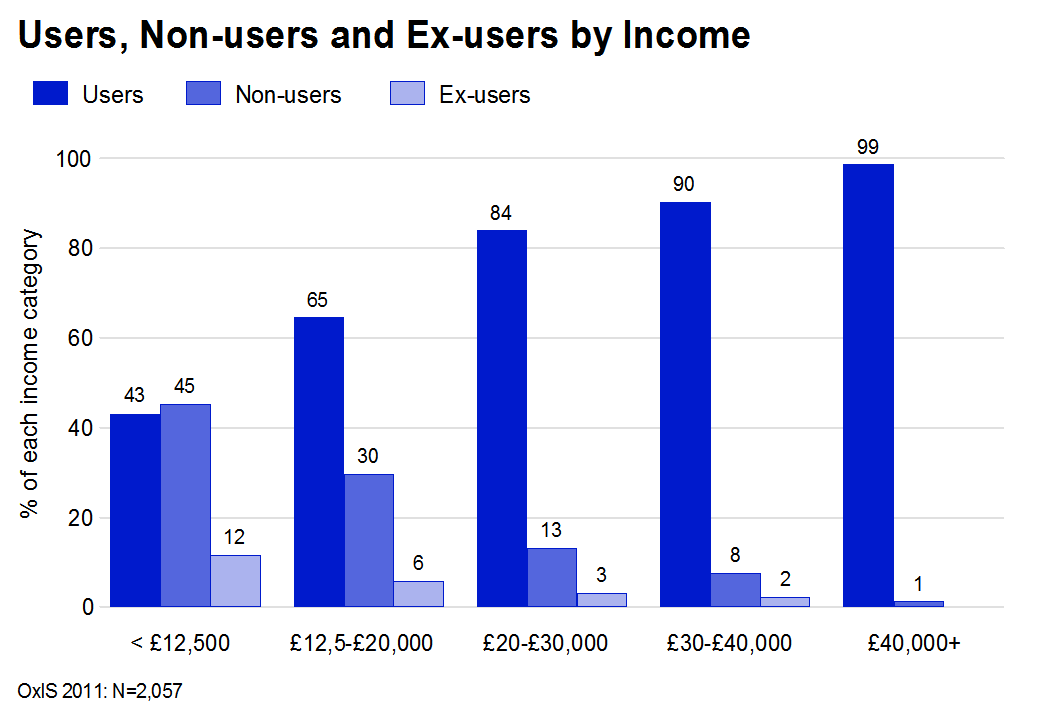

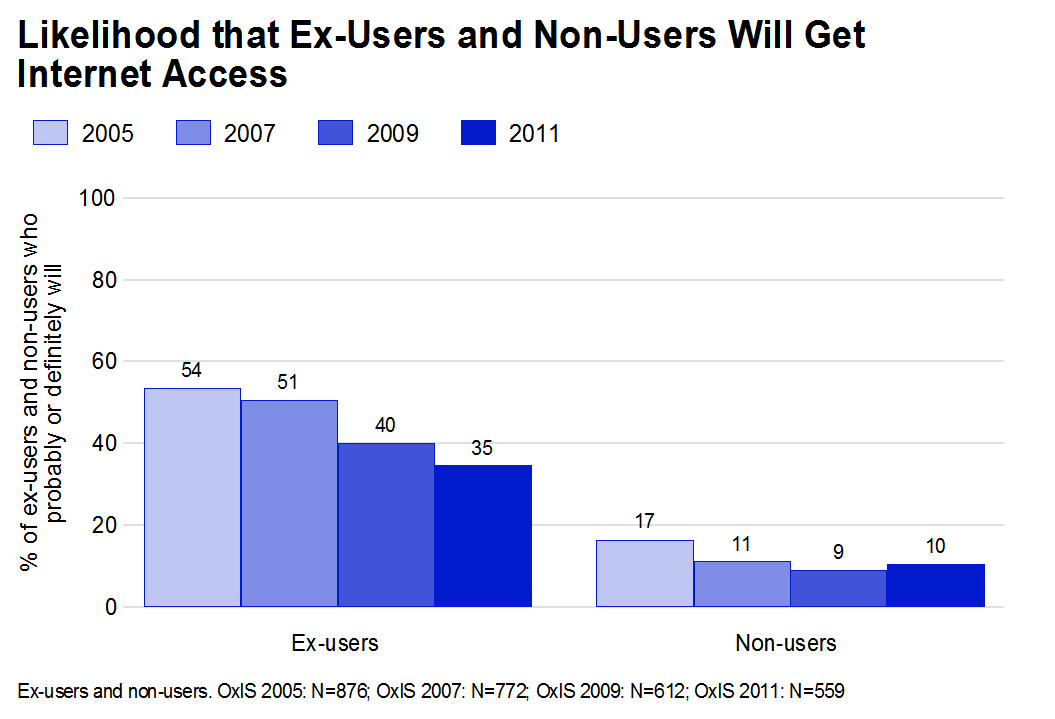

However, for younger citizens, who have used the Internet at school and have grown up with the Internet as a part of normal life, not using the Internet or using the Internet in limited ways is more likely to be linked to issues such as the costs of going online. The majority of this group do not need to be nudged into using the Internet.

Preliminary findings of our ‘Lapsed Use of the Internet Amongst Young People in the UK’ project confirm this hypothesis. They suggest that particularly young people in transition often find it difficult to get access to the Internet. These are young people who just left school and don’t have Internet access at home, young people who are in transitory homes or homeless, young people who have just arrived in the UK as a refugee and young people who are working part-time only, or are unemployed and therefore cannot afford to access the Internet.

“Sometimes the computers are full, so I go to the British library and can check my email and can see whether I have received something, because at the moment I am looking for jobs. If I am waiting for something important or if I have applied for a job…I have to keep checking my Internet and if I don’t have access to the Internet I really worry.” [Alexandra, 20]

“They actually cut the funding. And this is why places like the youth club here and Connexions that used to be open are no longer open, and the one-stop shop in L, all got their fundings cut, and they closed down. And, they, I’m surprised this place [youth club] is open, you know. But what can you do? Nothing, you would have nothing. You would seriously have nothing…” [Giorgio, 23]

Young people in transition are particularly at risk of being both socially and digitally excluded. Because of the restriction of their resources, accessing the Internet for them is not typically a matter of choice. This is why an ICT strategy based on choice architecture is not going to work for the majority of young people who are currently ex-users or non-users of the Internet. Instead, there is a danger that digital by default strategies doubly disadvantage those young people without Internet access, by aggravating and slowing down their enrolment process for government services and job programmes.

Therefore, strategies need to be developed that target young ex- and non-users of the Internet specifically, to ensure that these young people who are already part of an ‘Internet by default generation’ do not slip through the net, both technologically and socially.