Written by Grant Blank, William H. Dutton and Nico Buettner

You don’t need to be literate to use the Internet. Children, even infants, can use the Internet and social media at some level. Video news services and voice search are making reading and writing more optional for more Internet users. However, does effective of use of the Internet for pubic and commercial services – all critical in the digital age – still depend on traditional forms of functional literacy? And if so, has the research community’s focus on digital divides in access and multimedia skills deflected attention from even more basic competencies in reading and writing?

Many people might believe that literacy is no longer an issue in developed nations. However, even in the United Kingdom with free and compulsory primary and secondary education, functional literacy cannot always be assumed. According to the OECD, 1 in 6 adults in England possess very poor literacy skills (Kuczera et al. 2016). Illiteracy is highly consequential in modern societies. For example, the National Literacy Trust (2018) notes that boys from the area with the highest illiteracy in the UK, Stockton Town Centre, have an average life expectancy that is 26 years below boys living in Oxford, one of the most literate areas. While scholars have conducted extensive research on the link between illiteracy and a variety of socioeconomic factors, little is still known about how functional literacy relates to online behavior.

Based on the Oxford Internet Survey (OxIS) it is clear that functional literacy is strongly associated with general internet use and seeking out public information via the internet. In addition, compared to the fully literate, the less literate are less likely to agree that technology makes their lives easier and find it more challenging to keep up to date with new technology. This has important consequences for both the government and private companies that increasing move access to important goods and services online.

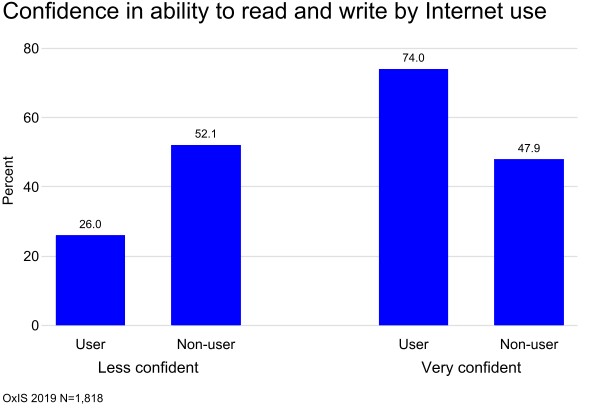

The British government’s digital strategy for 2021-2024 proposes that an increasing number of government services should only be available online. While this plan may be welcomed by digital natives, it prompts the question of whether this deepens the digital divide – one of the most basic indicators of inequality online. We asked “How confident are you in your ability to read and write?” The bar graph below shows that non-users tend to be less confident. Respondents who are very confident in their reading and writing abilities are much more likely to be Internet users. 74 percent of users are very confident compared to about 48 percent of non-users. Literacy is important when people use the Internet. To link our text to the text of the question, we will refer to respondents who report they are more literate as “Very confident” and those who are less literate as “Less confident”.

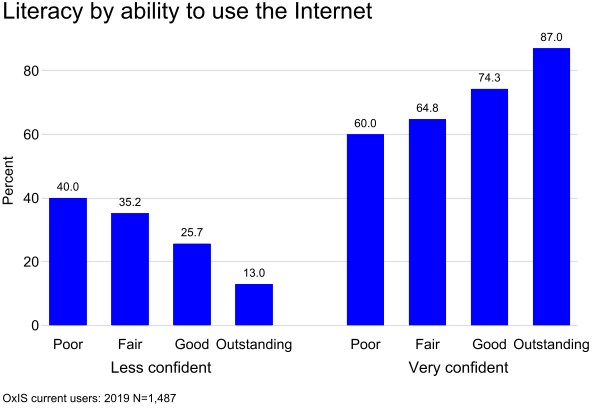

Perhaps the second most critical indicator of inequality online is one’s ability to use the Internet. Of course, we would expect those who are skilled online to be more likely to be functionally literate and the bar graph below shows that this is the case. Almost no one in our sample claims to lack confidence in their ability to read and write. However, these literacies are not identical. For example, a small number of individuals say their ability to use the Internet is good or outstanding have little or no confidence in their ability to read and write. Likewise, a small number who rate their ability to use the Internet as poor say they are very confident in their ability to read and write. So both the digital divide in access and ability to use the Internet are strongly associated with functional literacy. What are the implications for access to services?

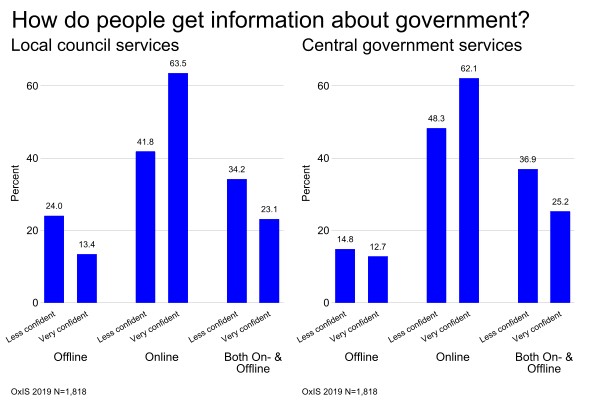

This literacy divide in access and skills has repercussions when we look at Internet activities. We looked at two kinds of activity. First is how people find out information about government. The responses show much the same pattern for both local council services and central government services. The bar graph below shows that respondents who are very confident are 22 percentage points more likely to get information about local council services exclusively online compared to the less confident. They are 14 percentage points more likely to access central government services online. Respondents who are less confident in their literacy are more likely to use only offline information sources for both local and central government information. The difference is about 10 percentage points for local council services and two percentage points for central government services. Less confident respondents are more likely to use a combination of online and offline sources by about 10 percentage points. Functional literacy has major effects on whether people use the Internet to gather information from all levels of government.

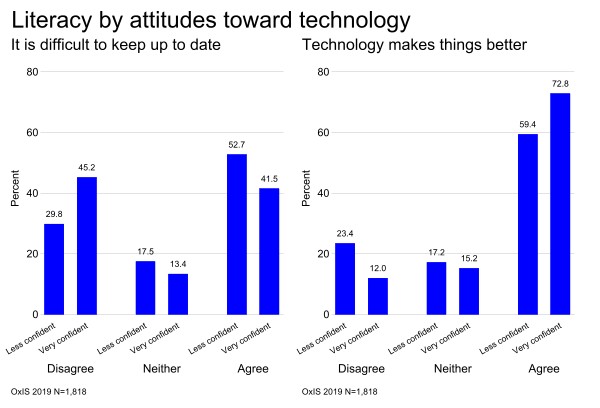

One reason for these divides could be that the less confident find new technological developments challenging and consider them less beneficial. We asked respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement “I find it difficult to keep up to date with new technology”. We find that the less confident do find new technologies more difficult. The left bar graph below shows that 53 percent of the less confident in their literacy agree compared to 42 percent of the very confident. We also asked for agreement or disagreement with “Technology is making things better for people like me”. The very confident are more likely to agree. The right bar graph below shows that 73 percent of the very literate agree compared to 59% of the less literate. This is a notable difference of 14% percentage points. Confidence in one’s ability to read and write appears to have a strong effect on attitudes toward technology.

Our results suggest that functional literacy could be a key impediment to a significant proportion of the public’s access to the Internet and public services. This raises questions about the government’s plan to make public services and information “digital by default”. This goal mirrors a similar trend among private companies that may require, for example, submission of job applications only online. While we agree that online services are valuable in and of themselves, and potentially cost saving, it is important to consider that increasingly moving such content online may have a disparate impacts on those who are already most vulnerable. In this light, developing effective interventions that help people to achieve full literacy becomes all the more pressing.

* * *

Our data were collected as part of the 2019 wave of the Oxford Internet Survey (OxIS). They are a random sample of individuals living in England, Scotland and Wales. Interviews were conducted in respondents’ homes during January-March. The total sample was 1,818 respondents. The number of Internet users was 1,487. All the results are weighted by age, gender and region to match population proportions.

Sources cited:

Kuczera, M. F., Windisch. S., Hendrickje C. (2016). Building Skills for All: A Review of England. Policy Insights from the Survey of Adult Skills. OECD Skills Studies. Retrieved 23 August 2021 from https://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/building-skills-for-all-review-of-england.pdf

National Literacy Trust (2018). Life expectancy shortened by 26 years for children growing up in areas with the most serious literacy problems. Retrieved 21 August 2021 from https://literacytrust.org.uk/news/life-expectancy-shortened-26-years-children-growing-areas-most-serious-literacy-problems/